In Behalf of the Ontological Argument

A defense of the argument according to which God’s existence can be known by way of conceptual analysis alone

Introduction

According to the Ontological Argument for the existence of God,1 God’s existence can be deduced by analysis of the concept of God: from God’s omni-perfection, so the argument goes, it follows necessarily that God exists, given that really existing just is part of being perfect in all respects. While the argument registers with many as a kind of elaborate word game or philosophical parlor trick, it has fascinated philosophers for nearly a millennium.

Contrary to a popular line of critique, the Ontological Argument has drawn more than a few people towards theism. I am one such person, which is why the argument features in my post, “Fifteen Arguments for the Existence of God.”

In this post, I will offer a simple presentation and defense of the Ontological Argument as a serious and defensible argument for God’s existence, and one which standard theists who think that God is necessary, or maximally great, should regard as sound, even if they don’t find it persuasive.

1. Historical Roots

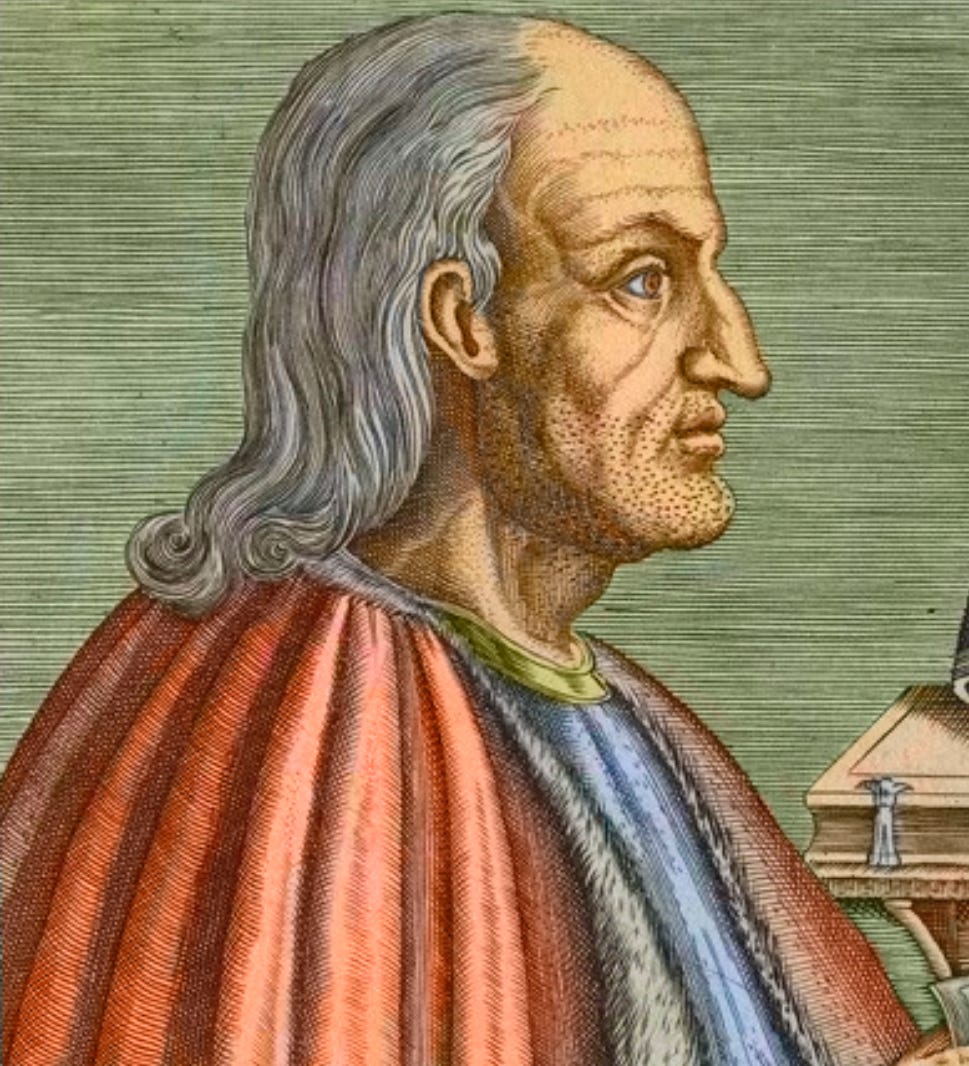

Unlike most of the arguments of natural theology, the Ontological Argument seems to have its origins in the thought of a single individual, St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) who formulates the argument as a meditation in his Proslogion (probably composed between 1077 and 1078).

Many thinkers since Anselm have offered various ingenious reformulations of the argument. These thinkers include: René Descartes,2 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,3 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel,4 Kurt Gödel,5 Norman Malcolm,6 Charles Hartshorne,7 Alvin Plantinga,8 Robert Adams,9 and Yujin Nagasawa.10

2. The Argument

The concept of God just is the concept of a maximally great being —“that-than-which-none-greater-can-be-conceived,” as St. Anselm himself put it. Plausibly, existence in reality (as opposed to existence as a mere idea in someone’s mind) is itself a perfection, or a great-making property. If so, then insofar as God has every possible perfection, then God must really exist — for if God were to exist as a mere idea, then a greater being would be possible (namely, one that really existed); however, by definition, no being could be greater than God (God just is the perfect being!). So, that-than-which-none-greater-can-be-conceived must actually exist. That is, God must really exist!

Some contemporary proponents of the Ontological Argument, such as the great Christian philosopher, Alvin Plantinga, have preferred to follow the legendary logician, Kurt Gödel, in formulating the argument by employing the resources of modal logic (the system for reasoning about possibility and necessity). Fully fleshed-out modal ontological arguments are technical and require a background understanding of modal logic to comprehend. However, the general idea is quite simple and is basically as follows. Given the logical coherence of the idea of a maximally great being (i.e., that it seems to entail no contradiction), it is possible that such a being exists. If it is possible that such a being exists, then, by definition, there is a possible world in which there exists such a being. But if there is a possible world in which a maximally great being exists, then the being exists in that world necessarily (since necessary existence is greater than merely possible, or contingent, existence) — in which case it exists in every other possible world (and, thus, the actual one). Therefore, a maximally great being exists.

Borrowing from a number of formulations of the Ontological Argument, we can distill it into standard form in a very simple manner as follows.

The concept of God just is the concept of a being with every possible perfection.

God is a possible being: the concept of God contains no contradictions (i.e., all of the possible perfections are compossible and so can inhere in a particular being).

Necessary existence is a perfection: a being which couldn’t fail to exist in any world is greater than a being which exists only in some worlds.

So, the concept of God just is the concept of a being which exists in every possible world.

So, God exists in every possible world.

So, God exists in the actual world.

So, God exists.

3. What’s So Special About the Ontological Argument?

There are at least three and important and unique features of the Ontological Argument.

First, there is the fact that if the Ontological Argument is sound, then it would directly secure the conclusion that God — an omniperfect being, not just a prime mover, an uncaused cause, a necessary being, or a designer — exists, and could not fail to do so. It is the only argument from natural theology of which that is true; with respect to all the other arguments, it’s open to the skeptic to wonder whether the initially established being (even if granted) is in fact God.

Second, if we are justified in confidently believing the ontological argument is sound, then we have a decisive answer to the problem of evil: for if we know that God exists of necessity, then we can also know that God has morally sufficient reason for permitting evils of precisely the sort that we find in the world. Absent such knowledge, the problem of evil is the thorn in the side of natural theology, for on their face, the bad-making features of the world militate against the belief that there exists an all-knowing, all-powerful, perfectly good being.

Third, if the Ontological Argument is sound, then revisionary models of God as some kind of limited being (as one gets from, e.g., pantheists [who identify God with the universe], deists [who often deny God’s omnibenevolence], and and open theists [who often deny God’s atemporality and impassibility]) can be simply dismissed.

4. Some Perennial Objections

There are, of course, many objections that have been raised against the Ontological Argument. I’ll briefly consider some of the more common and influential ones.

4.1 Gaunilo’s Objection: the Argument Admits of Refutation By Parody

In “In Behalf of the Fool” (which, in a philosopher’s attempt at humor, the title of this post plays upon), the French monk Gaunilo of Marmoutiers, a contemporary of Anselm, raises the worry that the form of Anselm’s argument can be used to prove the existence of all sorts of silly things — such as a perfect island (for if the perfect island did not exist in reality, then a greater one would be possible (namely, one which actually exists)!11

As Plantinga has noted, however, it’s not clear that the idea of a perfect island even makes sense. The great-making features of islands are agent-relative: my ideal island might differ from yours (I might like tropical islands, while you prefer desert ones). Moreover, it’s not clear that the great-making features of islands have defined upper limits: even supposing for the sake of argument that, objectively, palm trees make an island better, why should we think that there is any determinate number of palm trees that would be present on the perfect island?12

And likewise, it might be thought, with respect to a perfect anything-other-than-perfection-itself: God, in other words, might be relevantly disanalogous to any finite, contingent item, such that all attempts at refutation by parody will rest upon a fallacious analogy. God, perhaps, is unique. (Who would have thought?)

4.2 The Kant-Hume Objection: Existence Is Not a Property

The great Enlightenment Era skeptical empiricists, David Hume and Immanuel Kant, argued that the Ontological Argument is unsound because it rests on the assumption that existence is a property, and so can be predicated essentially of God. Whether a being exists, they thought, is distinct from the question of what are the being’s essential properties. If Hume and Kant are right then, contra Anselm, we can understand the concept of God perfectly well and yet reasonably wonder whether God exists.13

But: if existence is not a property, then what is it? What do we have that Frodo lacks if not existence in reality? I’ve never found a better answer to this question than a property.

4.3 God Is Impossible

It’s open to the atheist to dispute the initial premise, and thus deny the logical coherence of a maximally great, or necessary, being. Indeed, this is the objection which, by my lights, the atheist really should press — for if atheism is true, then God is indeed logically impossible; the idea of God is in some way confused.

Demonstrating God’s possibility is a non-trivial task for the theist. However, a fair initial observation is that it would at least be surprising if all the brilliant theists of history — Origen, Augustine, Anselm, Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Descartes, Newton, Locke, Leibniz, Kant (yes!), Hegel, Gödel, Plantinga, et al. — have believed in a logically impossible being! It would also be at least somewhat surprising if all those seemingly sane people who have claimed to experience God immediately were merely in the grip of non-veridical experiences as of God.

Yes, recently (since atheism really caught on in intellectual circles in the past 150 years) there have been many brilliant atheists. However, it’s telling that many (perhaps most) of these atheists have either thought relatively little about God (in many cases because they were in the grip of logical positivism or scientism) or else had an utterly confused concept of God (e.g., see everything ever written about God by a “New Atheist”). Relatively few philosophically-informed atheists seem to have thought that the God concept contains internal contradictions. And although some people claim to have experienced the absence of God, it’s not clear that one even could experience such an absence. (What would that be like, and how would it be distinguishable from merely failing to perceive God?)

4.4 The Argument Begs the Question

A favorite criticism of the Ontological Argument is that, even if sound, it begs the question, insofar as — however formulated — one of its premises will be too close to the argument’s conclusion.

This objection doesn’t move me all that much, in part because although the fallacy of begging the question is a perennial favorite of irreverent philosophy undergrads (like my younger self) looking to shoot down the arguments of great philosophers, it’s not really clear what the fallacy amounts to. All deductively valid arguments, by their nature, are structured such that if their premises are true, then their conclusion must follow — thereby having a degree of circularity built into them. Now, it’s of course bad and silly to literally restate a premise as a conclusion — but no serious statement of the Ontological Argument does that.

4.5 The Argument Is Unpersuasive

A related worry is that even if sound, and not formally question-begging (whatever that means), the Ontological Argument lacks persuasive power — and the purpose of an argument is not merely to support a conclusion, but also to persuade. This objection can be interpreted (a) as an empirical assertion about the way the argument in fact affects people or (b) as a normative claim about how it should affect people.

Interpreted as an empirical assertion, the objection fails, as an earlier remark suggested: some great thinkers have been persuaded by the Ontological Argument — the aforementioned Yujin Nagasawa being perhaps the best-known contemporary example. Even the great Betrand Russell, it seems, was convinced by the argument for a time (once exclaiming in a moment of epiphany while walking on the Oxford lawns, “Great God-in-boots, the Ontological Argument is sound!”) — before he wasn’t (Russell's philosophical commitments were as flexible as his marital ones).14

Interpreted as a normative assertion, the objection would have to be parasitic on some other objection — because if the argument is sound and not question-begging, then there’s no reason it shouldn’t persuade someone!

Conclusion

In conclusion, I think the Ontological Argument is not only philosophically interesting or persuasive only to those who are already convinced theists, but that it’s a genuinely serious argument for God’s existence. It deserves as much respect as the other classical arguments for theism, and anyone who (a) thinks the God concept is logically consistent and (b) thinks this concept necessarily is the concept of something with either existence in reality or necessary existence ought to endorse it outright. Certainly the stock objections wielded against it are by no means decisive. The ninety-ninth Archbishop of Canterbury just might have been onto something after all.

I do take it to be a single argument which can be formulated in innumerable different ways.

See Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy, “Meditation Five” (1641).

See Leibniz’s New Essays Concerning Human Understanding (1709).

See "The Ontological Proof According to the Lectures of 1831" in Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion, Vol. III, edited by Peter C. Hodgson, translated by R. F. Brown, P. C. Hodgson, and J. M. Stewart, 351–358, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

See “Ontological Proof" in Collected Works: Volume III: Unpublished Essays and Lectures, edited by Solomon Feferman et al., 403–404, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

See Malcolm’s “Anselm's Ontological Arguments", Philosophical Review 69, no. 1 (1960): 41–62.

See Hartshorne’s Anselm's Discovery: A Re-Examination of the Ontological Proof for God's Existence, La Salle, IL, Open Court, 1965.

See Plantinga’s The Nature of Necessity, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

See Adams’s "The Logical Structure of Anselm's Arguments”, The Philosophical Review 80, no. 1 (January 1971): 28–54.

See Nagasawa’s Maximal God: A New Defence of Perfect Being Theism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

See Gaunilo’s “In Behalf of the Fool” (1078).

See Plantinga (1974).

See Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779).

See The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, vol. 1, London: Allen & Unwin, 1967, p. 63.

As a Thomistic theist I appreciate your works very much! I have been “agnostic”over the validity of ontological arguments until recently when Joshua Rasmussen’s new Gödelian version moved me towards an affirmative position quite a bit more.

I am slightly worried about your treatment of “existence as property” in one of the objections. It seems to me that the Kantian objection is not the best way of framing it indeed, but a Thomistic framework can do it better: for any being its “being/existence/is-ness” is the foundation of all its properties, and is prior to all such. A being has an essence, namely the what-ness. The key problem, through this scope, of St Anselm’s argument to me is that it requires the “addition of an act of (real) being” to a conceptual being, but then there is no guarantee of the “conceptual God” and the “actual God” sharing the same essence (what-ness).

Note that I am not arguing that “one can not go from concept to existence”, far from it: Rasmussen pointed out that this is false since the concept of truth entails the existence of truth, and the concept of a concept entails the existence of a concept!

However, I believe the later developments shun this issue successfully to some extent. Plantinga starts with God as a possible being, then one can probe into the nature of its being (necessary or contingent), or as Gödelian arguments (like Rasmussen’s) starts with a perfect being which is either impossible or necessary, and argues against its impossibility via characteristics of “positive property”.

Speaking of What Matters or Matter please check out this reference:

http://www.integralworld.net/reynolds16.html